On Oct. 23, in the fifth webinar of China Macro Group (CMG)’s 2024 “Staying in Dialogue with China” series, Prof. Yu Miaojie, President of Liaoning University and Fellow of IEA, talked about China’s “economic globalization” as a fifth structural transition as per CMG’s conceptual framework of China’s political economy.

China in the 1980s embarked on a gradual and selective path of opening up its by then closed economy to the world – understanding that foreign investment and technologies were critical to the country’s catch-up development. In the years that followed, most notably after China acceded the WTO in 2001, the Chinese economy rapidly integrated with the world across trade and investment and started its climb in global value chains. At the same time, foreign investment flocked to China to make use of a skilled and comparatively cheap workforce, and in later days increasingly of a highly competitive and dynamic manufacturing and innovation ecosystem. A classic win-win situation.

Around 2015 (publication of “Made in China 2025”), and especially 2016 with the election of US-president Trump, however, the US and increasingly also the EU and other countries started pushing back against China’s export-oriented development model that had run large annual trade surpluses and become a significant economic player and competitor internationally in a number of industries. China, in turn, with the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) unveiled its ‘dual circulation’ strategy to respond to a more complex global environment – among others in an attempt to make its own economy less dependent on external inputs and strengthen its overall resilience.

To date, the global economic integration has brought great benefits to China, but amid an altered geoeconomic and geopolitical context, how will top-level policymaking evolve? What does Beijing mean with “high-level opening up”? What are policy and market trends for the continued “going out” of Chinese companies? What will Beijing do about the issue of “overcapacity” invoked by many Western governments, as well as its structurally large trade imbalance? In view of some new trade policy measures of the Third Plenum, will we see a stronger trade diversion targeting the Global South? What importance do policymakers still assign to FDI and is it in China’s interest to provide a better level playing field domestically? How is China’s financial integration with the world going to evolve? What role shall and can the RMB play in all this?

Yu Miaojie is President of Liaoning University, University Chair Professor of Liaoning University, and Liberal-Art Chair Professor of Peking University. He serves as an associate editor of The Economic Journal, Review of International Economics, and editorial member for around 10 prestigious international academic journals. He also serves as the executive editor of International Trade (in Chinese), the official journal of Ministry of Commerce of China.

Professor Yu’s research includes international trade, open economy, and Chinese economy development. He has published more than 150 peer-reviewed papers and 22 books both in English and Chinese, including prestigious peer-review academic journals such as The Economic Journal, Review of Economics and Statistics, Journal of International Economics and Journal of Development Economics. His book “China-US Trade War and Trade Talk” wins the 2021 China New Development Award of the Springer Press. He has been the only Chinese scholar who was awarded the British Royal Economic Society (RES) Prize.

He holds his Ph.D. in economics from University of California.

Here is the transcript of the webinar:

“China’s export will – for geopolitical reasons – diversify away from the EU and the US, targeting more Asian countries”

A conversation with Prof. YU Miaojie, President of Liaoning University, University Chair Professor of Liaoning University, and Liberal-Art Chair Professor of Peking University.

This text is transcribed from a webinar hosted by CMG and edited for clarity and brevity.

***

Markus / CMG: Good morning in Europe and good afternoon in Asia and in China. My name is Markus Herrmann. I’m the Managing Director of China Macro Group, CMG. Very warm welcome to the fifth webinar of our third edition of the webinar series, Staying in Dialogue with China, a European-China initiative, today on economic globalization with Professor Yu Miaojie, whom I’ll introduce shortly.

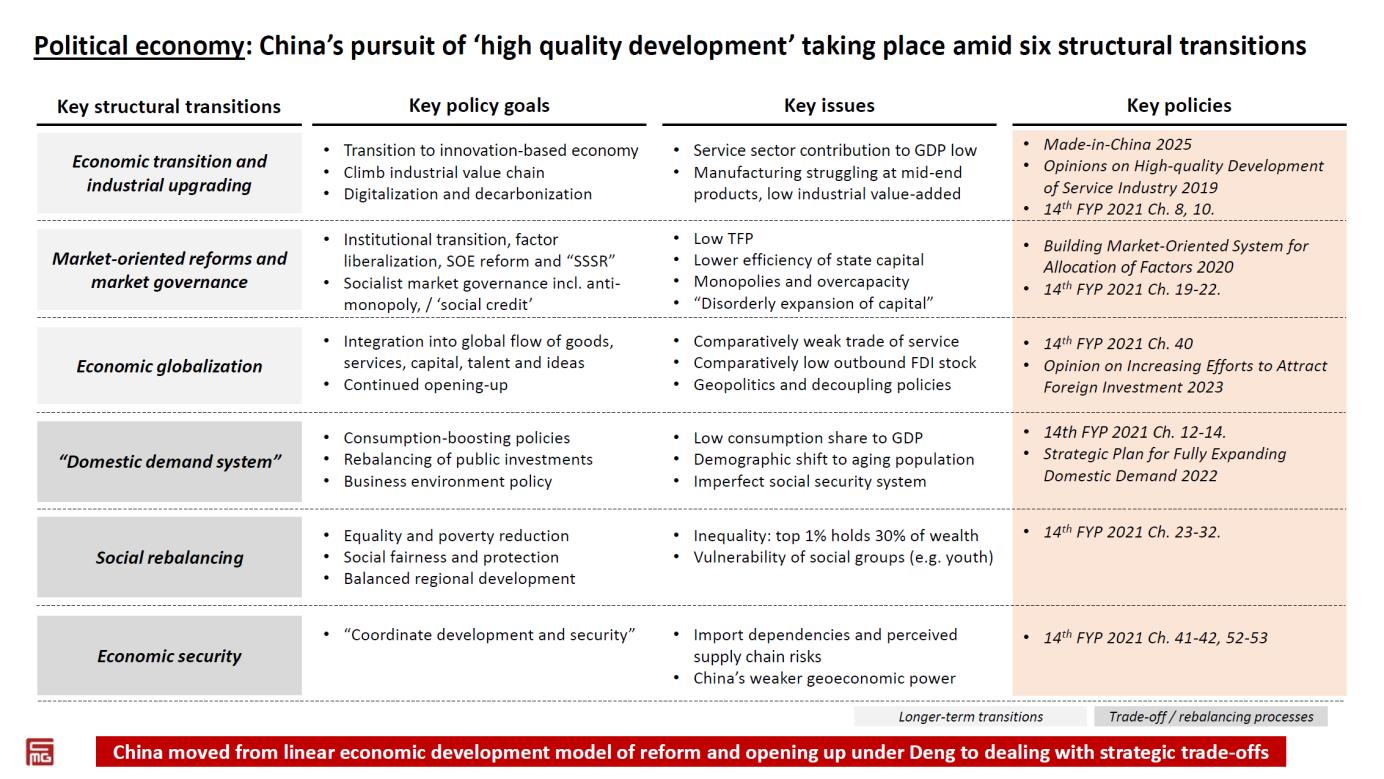

Our webinar series is structured along CMG’s political economy framework, inspired by input from scholars from PKU, which you will also find on our website and also in our different mailings. The six are economic transition and industrial upgrading, market-oriented reforms and market governance, economic globalization, the topic of today, domestic demand system, social rebalancing, which we had last time with Professor Li Si, and then also economic security. And we’re happy to debate and want to refine this framework along this webinar series, also with inputs today from Professor Yu.

This is the overview of the six webinars that we have been going through. And we’re very thankful for the cooperation with our Europe- and Asia-based partners to this webinar series. So, thank you very much.

And today’s focus is, as I was mentioning, on economic globalization with Professor Yu, whom I want to introduce now. Professor Yu is President of Liaoning University and University Chair Professor of Liaoning University, and he concurrently holds the Liberal Arts Chair Professor of Beijing University. He holds a PhD in Economics from University of California, Davis. His research focuses on international trade, open economy, and Chinese economic development. He’s a member of the Commercial and Trade Policy Consultant Committee of the China’s Ministry of MOF, and the International Poverty Reduction Cooperation Center of the State Council.

I also want to highlight a very recent piece of news. I think as of last week, Professor Yu has just been invited to serve as a deputy editor-in-chief of the world’s top publications in economics, making him the first Asian economist holding this position of the journal. I also learned that Professor Yu just took a high-speed train from Beijing to come back to Shenyang, where he is now, and from where he will speak to us. It took him only two and a half hours, and I quickly checked the distance. It’s the distance from Milan to Frankfurt. So, you had a speedy transition from Beijing back to Shenyang.

Finally, on the logistics, we have a minimum of 45 minutes and will leave enough time for Q&A. So please use this opportunity, type your questions into the Q&A box. We are recording the session today, but are not disseminating the video, but we will prepare a transcript that will be downloadable from our website.

Now, turning to Professor Yu, the first, general question, as this webinar series is structured along these so-called structural transitions, I want to ask you what you think about the framework of these six structural transitions, and is economic globalization for China a structural transition?

YU Miaojie: Thank you, Markus and good morning, ladies and gentlemen, I’m very happy that we have a chance to talk about the Chinese economy and particularly China’s opening up. So, let me come back to the question. I think China has already turned its gear from high-speed to high-quality economic growth.

You know, China, like many other countries, we are also facing several shocks. In the long run, we are facing the aging problem and de-globalization. In the short run, like many other countries, we are facing a weak demand and also got a negative supply shock. And because of the weak demand and negative supply shock, expectations are dimmed. However, we saw this year in July, the central government of China held the Third Plenum, announcing a resolution document with 15 chapters, 60 components, and 300 reform items. The idea can be encapsulated in five terms of China’s ‘High-Quality Development’: Innovation is the most important driving force, green is the common feature, coordination is an increasing characteristic, co-sharing is another objective, and, finally, opening up is a way must go. And, for sure, in this process, economic globalization is one of the most important structural transitions.

Markus / CMG: Thank you, Professor Yu. To set the baseline and understanding economic globalization broadly, inbound and outbound, for goods, services, talents, and so on, how would you characterize the state of China’s economic globalization today? Is China economically globalized, or very globalized, or just partially?

YU Miaojie: I think China is a very globalized economy. Let me give you some numbers: first, this year China’s total trade, including exports and imports, will be more than 6 trillion USD, converted into RMB this is 45 trillion RMB. Second, service trade this year we will be more than 80 billion USD, ranking China at number two globally, third, this year will generate more than 140 billion USD outward plus inward FDI, ranking China as the world’s number two or three. Fourth, China is the largest commodity trader globally. On top of these numbers and in terms of international cooperation, China is an important member of RCEP, is trying very hard to apply for CPTPP, plus is the initiator of the BRI. So overall, I would say China’s is having a very significant role in economic globalization. And I’m going to say, indeed, China plays a key role to lead the economic globalization.

Markus / CMG: Thank you, Professor Yu. What are the most interesting new trends in China’s trade policy?

YU Miaojie: China pursues what we call the “new opening up strategy”. It includes three components: a larger scale, a wider scope and a deeper level. What does this mean? First, when you look at the larger scale, you see that we are not only exporting final products, but now also intermediate products, because China’s labor cost advantage is diminishing. Second, when we say wider scope, we focus increasingly on cross-border e-commerce, digital trade and – what we call – green trade focusing on exporting China’s green or clean technology. Third, referring to the deeper level. What do we mean by deeper level? In the first phase of opening up, it was mostly leveraging China’s endowments, especially its labor-abundance, therefore you export labor intensive products. But now it’s about what we call institutional opening up: basically, we’re trying to learn from other advanced regional trade agreements, particularly on international rules, regulations, standards and their management.

Markus / CMG: A final question on the phenomenon of economic globalization more broadly. How would you compare China’s process of economic globalization to other developing countries or emerging economies?

YU Miaojie: I think that China certainly takes a lead here. Why is that? If we look at several perspectives, this will be clear. First, if we look at the size of China’s international trade volume, as I said, this year this will be 6 trillion USD, so certainly number one in the world, and therefore certainly number one compared to other developing countries. That’s one. Second, if you look at the opening up, particularly trade liberalization, China also takes the lead. For example, if you look at the simple average tariff, China this year is at 7.4%, while when you take the import-weighted tariff rate, China is only at 4.5%. Third, China’s opening up is not only beneficial to its own economy, but also to many other economies as well.

Markus / CMG: Thanks. Another example of opening up that has caught attention is the complete opening up of its manufacturing sector. What is the policy logic of this decision and why this timing?

YU Miaojie: Basically the logic is this way, first: the primary sector, agriculture, is about 8.5% of GDP, the secondary, including the manufacturing and construction, is 35%, the remaining 54-55% are services. So, what is the most important sector to create employment? It is not manufacturing, it is the service sector. However, if we ask which sector is the most important driving force to realize innovation, then it is manufacturing. So, it is manufacturing that will decide – if total factor productivity improvements are realized – if a country like China can escape the possible middle income trap.

Second, from the 1990s and then especially after 2001, China did open up step by step, with a focus on manufacturing. As the global economy is facing more complexities including supply chains, China’s competitive advantage is also changing: before, it was cheap labor as mentioned earlier, now it is increasingly the ability of Chinese firms to gain scale given the very large country.

Therefore, given the importance of the secondary sector, China focuses its opening up efforts on manufacturing.

Markus / CMG: I would like to pivot to the broader question of how opening up and reform can be pursued in a context of intensifying geoeconomic factors, like the EU’s “de-risking”, US’ export controls, proliferating FDI screenings, plus China’s own “de-risking” policy principle of “coordinating development and security”, or in the context of opening-up to “coordinate opening-up and security” (统筹开放与安全)?

YU Miaojie: First of all, this is a great question. Let me talk about the relationship between security and opening up. So, the short story is that security is the guarantee of opening up, while opening up is a way to promote security. So, this is their inter-relationship. But what is security? We define security as focusing on five things. Number one is national security, as many other economies and countries, that’s very simple, second is food security, three is energy security, four is technological security and five is ecological security. So, this is what we call security. It basically means that you only open up when you are guaranteed to have better security. But that’s the key idea.

Markus / CMG: How are China’s exports and imports evolving amid these increasing geoeconomic frictions?

YU Miaojie: First, China’s export will – for geopolitical reasons – diversify away from the EU and the US, targeting more Asian countries. So, for example, if we look at last year’s data, ASEAN is already China’s most important export partner, followed by BRICS countries and BRI countries.

Second, China will put more emphasis on importing more from third countries, enlarging the scale of imports. And this is truly important for China. China has never been a country that is just chasing a trade surplus. Indeed, China is trying to enlarge of the scale of imports very much. For example, next month, China is hosting the seventh CIIE, the China International Import Exposition. So basically, we’re trying to import more from other countries. And why is this important?

Three reasons: first, because in the domestic market, consumers can enjoy more variety, which is also a very good time to lift their happiness – in economics, we call it increasing the “consumer surplus”, or just “to make people happier”. Second, if you look at it on the corporate level, if you import more intermediate inputs and are able to combine these with your domestic inputs, then you can simply have a better final output for both China and the rest of the world. Third, certainly if you import more then you get more competition from these imports, and we are fine with competition. This means that the successful ones remain and get stronger and stronger, so the overall industry productivity increases.

Markus / CMG: What do you think about investing in China?

YU Miaojie: I still think that China is the most important investment destination. Why is that? First, China’s market is large, second, China’s overall labor cost and other costs are still relatively low, and third, also very important, China has a complete industrial system. The third reason is really important, especially for those in capital-intensive industries. And fourth, if you compare with other countries, I would say China is the safest place to invest. You do not need to worry about your personal security. Fifth is about China’s broadening international cooperation and connectivity like the BRI, plus it continues to provide more public infrastructure.

Markus / CMG: Thank you, Professor Yu. Can you expand a bit more on the complete industrial system?

YU Miaojie: For capital-intensive industries, the most important factor of production is not labor, but whether you have a complete industrial and supply chain. And that is the most significant advantage of China’s system, because we know, if we look at China’s industrial system systematically, we have 41 SIC two-digit industries, and 207 SIC three-digit so-called middle industries, and finally 606 SIC four-digit final industries. China is very likely the only country in the world that has this complete industrial system. And this guarantees that if you are in a capital-intensive industry, you will come back to invest in China.

Plus, there is another factor: local governments have a lot of policies to attract and support FDI. For example, between 1979 to 2013, in those past 34 years, China had been treating foreign firms much better than its domestic firms. We call it “super national treatment”. For example, domestic firms pay 35% corporate tax, while foreign firms only 17%, plus in the first two years they do not pay any corporate tax at all.

Markus / CMG: How do China’s self-reliance (自立自强) needs impact imports, as you mentioned earlier that national security is a legitimate need of large countries? What do you think is the net effect between a CIIE promoting imports, but at the same time strategically you want to have self-reliance?

YU Miaojie: Self-reliance needs are needs where China needs certain products but some countries deny it access through export controls. And suppose we do not produce those products, then we are not able to have those products. And even when we try to buy them, you cannot buy them because people don’t want to sell to you. So, you need to do self-reliance in parallel with increasing the scale of imports. Yeah, so that’s the point.

Markus / CMG: How does the party or government see economic globalization conceptually today? What’s the official term, is the world economically de-globalizing, re-globalizing? What is it?

YU Miaojie: Yeah, so that’s really important. If we study the Third Plenum, we see that it’s very clear.

First, we all understand from Marxist philosophy that the economic foundation determines the “upper infrastructure”. So, what is the economic foundation? China’s judgment is this way: we’re trying to have what we call inclusive and beneficial globalization. Certainly, we see that there’s some trend of de-globalization, like some country raised very high tariffs against other countries. But we think globalization is still the most important trend.

Why is that? Because the two most important features of globalization are still there: local specialization and international trade. Why is that? If you look at the first one, say the local specialization, look at your cell phone, doesn’t matter it is Huawei or Apple, each component is produced by one country particularly, for example, your camera, or your CPU. This is what we call the local specialization. But eventually all products come back together, and you need a destination to do the product assembly, maybe before or currently this is still in China, but maybe later it will be in Vietnam or other countries. But it doesn’t matter, once you produce this product, you sell to all countries in the world and this is called economic globalization. And we see that despite protectionism it doesn’t fundamentally change. So, basically what we say is that we want the supply chain not to be biased to one particular country, we try to have it beneficial to all countries and be inclusive, not exclusive.

Second, then, what is the “upper infrastructure” of this economic foundation in international trade? We believe it is what we call multipolarity, i.e. not only one country, like the US, EU, China or others, or whatever, any other countries. It’s not China or the US, basically the idea is the order should be a multipolar order, not a chaos. And it should be something equalizing, it can’t be something very unequal where some countries get a lot of benefits, some countries only lose. So, in brief, my understanding from a trade perspective is that we need to have inclusive and beneficial economic globalization, leading to equal rights and a multipolar order.

Markus / CMG: How do you see the issue of “so-called” (所谓) overcapacity?

YU Miaojie: I think this is very confusing for many people. The basic argument says: well because China has overcapacity and is therefore dumping to other countries, therefore these countries can erect high tariffs against Chinese products. For me, I think this is incorrect. Why is that?

First, what’s the definition of overcapacity? Suppose a firm is able to produce 100 products, but is only selling 80 products. Then basically I say, well, we have 20% overcapacity. By defining this, we see countries like the US and the EU, and also China have overcapacity. Precisely, according to data from 2000 to 2020 the EU is about 82%, the US about 79% and China is 77%. So, China’s number is a little bit lower, but more or less, they are the same. So statistically we do not have a big difference.

Second, why do we have overcapacity? It’s because of the weak demand. It’s not the opposite, it’s not because you produce too much and you’re not able to sell, but what I want to say is because the domestic and international markets are both weak and therefore you are not able to sell. Look at 1929 to 1933 the Great Depression, at that moment it is certainly because of weak demand, not because of overcapacity.

Third, some people say China has industrial policy, offers subsidies and therefore has overcapacity. Does China have industrial policy? Yes, the answer is yes. But once again, is it only China that has industrial policy? Certainly not. If you look at the US, they certainly try to have a lot of industrial policy or Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. So, I do not think it is only China that has industrial policy.

Fourth, we need to ask whether a subsidy policy violates WTO regulations. The answer is it depends on what kind of industrial policy, or it depends on what kind of subsidy. If this subsidy is trying to promote R&D, it’s trying to protect the environment, it’s legal and in line with the WTO. It’s called the Green Line. And that’s good, right? So, I mean, China has industrial policy on NEVs, for example, but they are trying to protect the environment. They are trying to reduce CO2 emissions. So, I mean, it is legal.

Markus / CMG: What about China’s domestic demand? And can China just premise its growth on international demand? Isn’t that too ambitious?

YU Miaojie: From China’s domestic side, basically, if the international demand is weak, what can Chinese firms do? Especially as the Chinese government is trying to foster domestic demand and try to have what we call the big domestic unified market. If you look at the US, foreign trade is more or less the same as in China, but their trade over GDP is only 25%, because their domestic trade is 75%. On China’s part, if you look at 2007, before the financial crisis, we got even 70% of foreign trade, which now decreased to about one third, so one third foreign trade and the domestic trade is two thirds. So, we try to learn from some other countries like the US about how to increase the size of domestic trade from two thirds to three quarters. That’s why the unified domestic market is so important.

Markus / CMG: What are then the main traders domestically?

YU Miaojie: First, seen through the lens of GDP components: Guangdong is the most important export province. Zhejiang is the most important consumption province. And the northern provinces are the most important investment provinces. But if you ask which province is most important for domestic trade, I would say Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Jiangsu.

Markus / CMG: Facing US export controls, what do you think is the overall attitude of the Chinese government?

YU Miaojie: China wants to work with everyone, but it is denied certain key components. We have 1.4 billion people, we want to have what we call economic globalization, and that this economic globalization is inclusive and also beneficial. So, this is the starting point. And then because of this, China is trying its best to promote trade globalization. When you look at the central government’s document, they still clearly say that “peace and development” are the themes of our times.

Markus / CMG: A question from an online participant: How does China view CBAM, the carbon border adjustment mechanism?

YU Miaojie: I think this is a little bit complicated. I’m only talking about my own observation. I do not think that CBAM is fair. Certainly, this is a very nice idea, but then if you’re talking about this idea to some developing countries like Brazil or Indonesia, they will say, well, maybe development rights are also very important. And they will say, well, if you want to impose the tax, then who should pay it? Is it the supply side or is it the consumer, right? So fairly speaking, I think that if you want to have a tax, so how to draw a line between the producer and the consumer, that’s the most crucial one.

Markus / CMG: Towards the closing, what worries you most in China’s and overall economic globalization?

YU Miaojie: We think economic globalization is most important for China’s development, but we have, as you say, intensifying geoeconomic factors. And once these factors enlarge, then it’s dangerous to weaken the base of economic globalization. And then I think what humans learn from history is that they do not learn from history. So, if you look at what is happening right now, it is very similar to 100 years ago, 1914.

And we all understand what happened in 1914. Plus, we also all understand what happened in 1939, right? So, we don’t want to go there. Because of this, I think some country will gain, some country will lose, and some people will gain, some people will lose from economic globalization, but for the entirety of countries, all gain from economic globalization, that is what we learned from Adam Smith and Ricardo. So, I still think that free trade is the best. And we hope that we have a better tomorrow for everyone.

Markus / CMG: Okay, what a closing with Smith and Ricardo in these geo-economic times. Prof. Yu, thank you so much for taking the time and walking us through a broad set of questions and sharing your viewpoints.

For reference: CMG’s political economy framework: six structural transitions